An Army Marches on Its Stomach

- Nathan Decety

- Jul 24, 2021

- 25 min read

Updated: Jul 24, 2021

Is morale everything? A study of factors to military success through Tolstoy’s War and Peace

This essay won the Marine Corp's Commanding General's Writing Contest in 2018

In Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace there exist two tensions: whether leaders have the capacity to direct events and the importance of strategy versus morale. Throughout the novel, Tolstoy makes it clear that leaders are tools of history–their actions are formed and guided by their environment, not by reason. He argues through characters that the “science” of strategy is nearly meaningless, while the morale of soldiers is far more important, where ‘morale’ as an abstract concept is made of myriad of individual wills and feeling. These arguments have several flaws; partly because of contradictions within the novel, and partly through logical analysis based on historical events and human behavior. These tensions apply directly to the Marine Corps’ perspective of command, discussed extensively in doctrinal publications such as Warfighting and Marine Corps Tactics, as well as works in the Commandant’s reading list, most notably Command by Van Creveld. In this essay, we will discuss these tensions with a thorough analysis of the individual, his response to his environment and other individuals at various stages of command and attempt to arrive at a rational conclusion.

Section 1: Tolstoy’s Beliefs

Through Prince Andrei, examples of men in battle, and the narrator, Tolstoy expresses his beliefs of what decides the fates of battles. Tolstoy demonstrates that reason and forethought–the tools of the commander–have no place in determining the outcome of a battle or campaign. The ideas are most fully exposed in Prince Andrei’s argument with Pierre before the battle of Borodino:

In chess you can think over each move as long as you like, you’re outside the conditions of time, and with this difference, too, that a knight is always stronger than a pawn, and two pawns are always stronger than one, while in war one battalion is sometimes stronger than a division and sometimes weaker than a company. Nobody can know the relative strength of the troops…. “Success never did and never will depend on position, or on ammunition, or even on numbers; but least of all on position.” “But on what, then?” “On the feeling that’s in me, in him” he pointed to Timokin, “in every soldier.” (773)[i]

Part of the reason why morale is so decisive is because all other factors grounded in logic are incorrect, for the conditions of battle are always in flux–making the commander’s role useless or counterproductive during a battle. Morale contributes to Tolstoy’s larger idea expounded in War and Peace of fatalism in history. Tolstoy argues that “everything happens by itself,” that no action could have occurred otherwise–that actions are far more important than the individual; that it is impossible for individuals to change the course of events. We challenge Tolstoy’s arguments, with the idea that while morale is indeed important in winning conflicts, there are substantial factors related to ones morale in a battle, factors which are affected greatly by the environment, command, position, training, and reason.

Section 2: Are feelings everything? Reason in making decisions.

When an individual performs an action in War and Peace, he or she is not driven entirely by emotion. Emotion is a part of the action, often a reaction to the stimulus of the environment. Even in the portions of the battle that appear to revolve around feeling alone, one sees the place of reason, substantiating the emotions that surround the thoughts and decisions of individuals.

We look first at Rostov’s seemingly impetuous attack on the French dragoons, an action to which we shall return often in this essay. Here, Rostov notices with ‘his keen hunter’s eye,’ an opportunity to rout the dispersed and disordered French dragoons. He then sought a subordinate officer and told him of his plan–albeit in broken up speech (to be expected in the heat of the moment): “you know, we could crush them… and the captain fully understood, “It would be a daring thing…” (653) After this communication, Rostov sets down the hill, followed by his hussars. Clearly Rostov took the time to observe and, with the aid of his prior experiences, which became lodged in his mind, reflected upon the feasibility of action. He communicated and acted. This is followed by: “Rostov did not know himself how and why he was doing it… not thinking, not reflecting.” It is possible that Tolstoy was writing about Rostov’s adrenaline rush, which he was likely to have. Yet taken as a part of Tolstoy’s argument, that people including Rostov act and could not have acted otherwise–following their feelings–this seems unlikely; instead a moment of rapid cognition, of adaptive unconscious, the focus of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink must have taken place. More pertinently, Tolstoy’s argument is clearly countered by the thoughts which passed through Rostov’s head leading him conclude that a charge should happen.

Away from the officer’s feelings we come to those of the soldiers, demonstrated at Schöngraben. Attacked by the French they are encircled by surprise. “One soldier uttered in fear the words: “Cut off!” – senseless and terrible in times of war – and the words, together with the feat, communicated themselves to the whole mass.” (190) The feeling of the soldiers manifested in their disordered rout, comes from a completely reasonable fear for one’s safety. If they are indeed surrounded, they can be caught in a crossfire which would result in death or capture. To understand that they are surrounded is not a product of irrational feeling but of rational consideration of the relation of the individual to the tactical unit within a specific environment.

Finally, we turn to the commanders exemplified by Kutuzov–a character Tolstoy insists acts upon ‘experience of life’ and ‘despised both knowledge and intelligence.’[ii] Yet in practice, we note that Kutuzov regularly acts in accordance with knowledge and intelligence. In fact, what is ‘experience of life’ if not the intelligence to remember what functions and what doesn’t, the compilation of which is knowledge (again, Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, notably Chapter 5)? Kutuzov does–as do all the other ‘interchangeable’ commanders–rely upon reason to make decisions. The most striking example is at the war council that decided to abandon Moscow to the French. Kutuzov listened to the variety of opinions around him, then chose the one which appeared most reasonable. He even deigned to object to Benningsen’s plan with an argument based on past events, “I cannot approve of the count’s plan. Shifting troops in close proximity to the enemy is always dangerous, and military history confirms this consideration…” (830)[iii] Clearly the rank and file in Tolstoy’s novel refuse to obey to the idea that feeling orchestrates change and that all actions, whether or not feeling is involved, is tied or based upon a bedrock of reason.

Section 3: to what extent is it possible to subjugate wills, especially with the fear of death in mind?

Tolstoy’s theory of history is based upon the idea that history is the aggregate of a multitude of wills–and therefore cannot be studied top-down, but must be studied from the perspective of the individuals that make up events. This idea reverberates in battle, as men fear for their lives and break before the threat of death. We shall not dispute the entirety of this argument for brevity’s sake; but, with respect to war, we must point out that Tolstoy’s ideas are flawed simply given the evidence within the novel. Without subjection of wills (i.e. people don’t do as they are told), it is impossible to wage war. According to Tolstoy, fear of death breaks that subjection. However we notice that it doesn’t, that throughout the book men willingly–even cheerfully–face death, showing that death itself will not interfere with the ability to follow commands, allowing for orders to take place in battle.

Russian officers–exemplified by Prince Andrei at Borodino and Austerlitz and the regimental commander at Schöngraben–display a total disregard for death performing their duties.[iv] Russian soldiers altogether felt more than happy to risk their lives for the Tsar–their wills entirely given to him by choice.[v] An even more obvious example is Napoleon’s Polish uhlans, who sacrificed themselves uselessly hoping to please Napoleon.[vi] Tushin’s battery, despite being wiped out, became more and more merry–not fearful–under the increasing threat of death.

These examples show that encountering death does not have to interfere with the will to follow commands, people do not follow commands either when the fear of death (which, once again, is rational) is more overpowering than their love, or duty, adrenaline rush and/or other emotions.

Section 4: Wills of the people coinciding with the wills of the general

If, following their reason, people’s wills do not coincide with their generals’, commanding troops becomes far more complex. Fortunately, troops in War and Peace tend to obey their officers except in the face of certain destruction;[vii] they perform their duty in battle as long as the chances to achieve them are high, chances which related to disposition, logistics, etc. (see the next section for a further discussion upon this topic). In the novel it is the commanding officers who attempt to erode the authority of whoever is higher for their own selfish reasons. Self-advancement is a theme throughout the book–many officers strive to show their courage and skill, while downplaying or tripping up their competition (such as Benningsen);[viii] or endangering themselves without purpose, which has negative results (such as Petya).

Ultimately leaders handle these events, minimizing the impact that they can have on the course of the campaign. Since leaders at the top of the command structure have their purpose aligned to the goals of the campaign (i.e. Kutuzov has nowhere higher to go, and so does not have to compete with others, his purpose is therefore to ensure the campaign goes well against the French).[ix] Just as a commander must deal with possible major obstacles, they must deal with dissent in the ranks to ensure that their will is followed for the good of the campaign. Despite the constant displeasure and disagreement with Kutuzov, Kutuzov is not dismissed–for whatever reason–from command of the Russian forces. As commander in chief, he does not allow any unreasonable action to occur, minimizing Russian losses to the best of his ability and exploiting mistakes the French make–[x] never bending to the pressure of his subordinates unless he himself is convinced.[xi] During battle itself, the enmities of men for each other fade away since defeat and death would mean the end of all parties. For example, the officers arguing at Schöngraben put aside their differences once they become encircled.[xii]

The way to undermine one’s competition involves attacks along the hierarchy. Bennginsen for example, attacks Kutuzov through the Tsar. It is then the up to the Tsar to act. As we saw in Section 2, his decisions would be quite rational, the result of being persuaded through reason.[xiii] Since he is at the top of the chain of command, the same actions necessarily regularly take place both in the army and in society as people seek self-advancement. The point is that these people seek help to rise from above, from the wills of those in higher places. Although they can sway the wills of those in charge through reasonable arguments, in a centralized organization, leaders are the ones who must act. It is therefore indeed possible to study what the multitude of wills can be through the actions of leaders who attempt to act in their nations’ best interests. In sum, the wills of the people who seek self advancement tend to matter little as they become aligned with the necessities of the campaign and wills of those who are highest.

Section 5: Importance of Position

Since individuals’ actions are related to and driven by reason, and that one’s feelings are connected to the environment, Tolstoy’s assertions that “success never did depend on position” cannot be the case. It is a radical simplification of the complexities of warfare. We note first that one’s position radically affects ones morale and capacity to act. Secondly, we note that one’s position and its suitability it is to the current conditions can change within an instant. It is how one responds to rising threats which can result in victory or defeat, and meeting the enemy on the most advantageous ground tends to lead to victory, as both Tolstoy and history demonstrate.

To return to our discussion of the infantry at Schöngraben, the Russian soldiers retreating chaotically were in fear of being cut off, “The left flank, which was simultaneously being attacked and encircled by superior forces of the French….” (186) Given the result of being encircled (panic and retreat), Tolstoy unwittingly acknowledges how positions impact the morale of soldiers. Another example is before the first major battle of the novel, Austerlitz. The French performed a variety of maneuvers to convince the allies of French weaknesses, thereby persuading the allies of the need to attack. As part of this plan, they abandoned the Pratzen heights. The allies believed them to be on the opposing heights, whereas the French were concealed below the heights, far closer than the allies thought. Furthermore, Napoleon’s right flank was shored up by supporting troops from a march away, an action the allies did not expect. These maneuvers and the strategic positioning of the troops, coupled with the allies’ overly aggressive and uninformed spirit resulted in a major surprise to the allies and their defeat at Austerlitz.[xiv] Had the allies known, for example, that the French were right below them, they would have formed up for battle as Kutuzov attempted to do on page 277, rather than march into battle in columns (not maximizing potential musket fire) and confusedly drawn up.

The other major battle, Borodino, is also a reflection of the importance of positioning. Whether or not the Russians wanted Shevardino to be their left flank (a topic still argued about) matters little. The Russians pulled back and reinforced their positions, which were obviously chosen to maximize the defensive capabilities of the Russian army, such as the elevations available on the left flank.[xv] The Russian position, though described by Tolstoy as weak, was quite strong–especially since the French attacks were focused on the major defensive works (we shall return to this in the next section).[xvi] The battle of Borodino, between the experienced and powerful French army and the ‘barbarian’ Russian army resulted in a ‘mortal wound’–as Tolstoy describes–to the French army. In turn the Russian army was able to retreat and continue to present a threat. Part of the reason the Russians were able to fight and damage the Grande Armée to this extent was due to their positions being able to provide a degree of safety and an advantage over the French (just as in past ages, those on ramparts have a fighting advantage over those attacking below).[xvii]

Beyond positions related to strength, dispositions also grant an ability to observe–whether that ability is put to use depends upon those at the scene, but it grants them an advantage over those who cannot have insight. For example, Rostov’s attack on the French dragoons was a downhill attack. Rostov could see the both the action and relative strength of the enemy.[xviii] On flat ground or uphill, Rostov would not have been able to see the opportunity before him with his ‘keen eye,’ and the action would not have occurred – perhaps had the French been on higher ground, they would have noticed the threat posed by the hussars and maintained their organization.

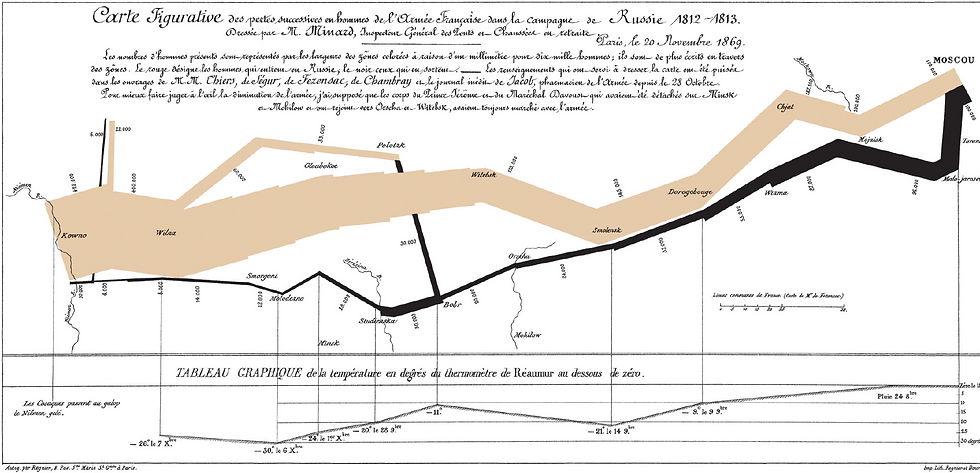

A final important factor related to disposition of armies relates not to battle, but logistics. Without food, men and horses become weak and die (see the French army in Rifleman Dodd). That is a fact not disputed by Tolstoy. Without ammunition, which runs out quickly in battle, men can no longer fight. As European fights against technologically inferior foes demonstrate (such as the conquest of Africa), having no shot and powder in the face of an enemy which does is almost always a death sentence on the battlefield.[xix] Without water and provisions, the French died off during the Russian campaigns–as many sources other than Tolstoy testify, see for example figure 1 for a visual representation of the steady French losses, or pages 766 and 780 in War of Wars for further description. Beyond weakness and death, a lack of resources affects the men’s morale; if the men know–since they are able to reason–that they will starve or be annihilated, they are far more likely to melt away, thereby decreasing the fighting ability of the army even more. Tolstoy explicitly recognizes the value of these factors on page 991.[xx]

Why did Mack surrender at the Ulm, having been outmaneuvered by the French? If we assume that position has no value in reality–as Tolstoy argues, and the action could not have happened otherwise (i.e. he could have had a better idea of the speed of French marching rates), then his decision was based on morale, a larger version of the aforementioned Russian left flank retreating at Schöngraben. If so, Mack’s army must have realized that he had no other option–his and his army’s morale were directly contingent upon their positioning and those of the French. Whether they were doomed, and that they had to surrender or die, or not, matters little if they were convinced it was true. Reason led the entire army to forfeit. At Borodino, although Russian and French losses were relatively comparable, the Russian army–because it was within its lands and close to supplies–could refill its numbers and retreat more or less safely, whereas each man the French lost could not be restored; akin to the difference between a wound that scabs and one that hemorrhages.

On a more conceptual level, certain terrain provide better position for troops, for example an elevated terrain provides observation abilities (as with Rostov’s hussars), can hide troops from enemy sight, and increases the reach of arms while decreasing the reach of an enemies due to the impact of gravity. We therefore note not only the importance of position on ones ability to fight with an advantage both related to practical factors, and for morale purposes–related to those practical factors. Men, imagining these factors to exist and believing that they make a difference allow these factors to impinge upon their morale, having a drastic effect upon the result of a battle.

Section 6: Importance of Generals and Commanders Before Battle

This discussion brings us to the question of the purpose and significance of generals with regard to campaigns. Tolstoy repeatedly and clearly disbelieves the ‘great man theory of history–’ to the point of noting the futility of leaders throughout the novel, such as:

“If we picture to ourselves, not commanders of genius at the head of the Russian army, but simply the army alone without any leaders, that army could not have done anything other than [what it did]…”(989) “By many years of military experience he [Kutuzov] knew, and by his old man’s mind he understood, that one man cannot lead hundreds of thousands of men struggling with death, and he knew that the fate of a battle is decided not by the commander in chief’s instruction, not by the positions of the troops, not by the number of cannon or of people killed, but by that elusive force known as the spirit of the troops… “ (805)

Tolstoy writes that is a passive repository of knowledge,

“He understands that there is something stronger and more significant than his will–the inevitable course of events…” (745)

Despite what Tolstoy says in his theoretical musings, he provides ample proof that challenges his own assertions. Beginning with Kutuzov, it is easy to see that he is indeed active as a leader both before and during battle–not an unassertive and somnolent old man as Tolstoy portrays him. As we saw in Section 2, Kutuzov is not guided simply by emotion but takes the time to choose an action, considering position as highly and with as much ‘military science’ backing his ideas as his more ‘unwise’ counterparts (we should not forget that–as mentioned above, no factor is independent of morale, everything impacts soldiers, which in turn impacts how they perform, affecting the factors once more, and so on[xxi]). In looking at these decisions, both Tolstoy and the reader notice the differences between an intelligent order issued by a general, and a stupid one with regard to movement.

Before the battle of Schongraben, Kutuzov is placed in a difficult position where each option bears considerable risk. He is presented with his options and chooses the one he thinks can carry the army to safety.[xxii] Indeed Kutuzov is often cited by Tolstoy as the only general attempting to keep the Russian army from engaging in a useless battle with the French during the French retreat from Moscow–battle which could and sometimes did result in disasters for the Russian army–Kutuzov’s logic continually saved Russian lives.[xxiii] In contrast to Kutuzov who happened to choose a path which ended up saving his army, Napoleon–in retreating from Moscow–chooses an idiotic path which was most unnatural for his army, contributing to its destruction: “he [Napoleon] used his power in order to choose, out of all the paths of action presented to him, the one which was the most stupid and destructive. Of all that Napoleon might have done… nothing stupider, or more destructive for his troops, could possibly have been thought up.” (1001) Reading this, we keep in mind the aforementioned quote about the Russian army ‘naturally marching where it did’ (989). If the Russian army ‘naturally’ marched where it did, why did the French also not naturally act in its own self-interest? Tolstoy answers this question, thereby proving that Kutuzov does not simply let ‘things happen’ but reasons quite well. Napoleon simply did not reason correctly, and his choice of a direction of march doomed his army. The deserters – those that did not wish to march in that direction – did not have sufficient strength or numbers to fight the Russian partisans around the army – and therefore also died.[xxiv]

Leaders therefore have an enormous duty towards their army with regard to position. Should they choose a ‘unnatural’ path–or one that places the army in a poor position (such as one where they are surrounded, or one where there is little food to be had). Beyond this, leaders also decide the timing. Napoleon decided to march out in October from Moscow, Napoleon decided to attack the Shevardino redoubt at dusk, and Napoleon chose the hour to attack at Borodino.

A final duty of leaders is to issue orders before battle. As expected, Tolstoy ridicules this final duty, arguing–essentially–that orders are impossible to follow and that a battle never goes according to plan. On one hand, Tolstoy makes a good point; no one has perfect and complete information–not the commanders in chief, nor the commanding officers or soldiers and mistakes are therefore bound to occur. On the other hand, the lack of perfect information does not mean that attempting to create plans according to reason is futile. What tends to happen is the friction and chaos (see MCDP1) of the moment changes the setting in which orders are carried out, obstacles arise which were not thought of beforehand and taken into account–in different shapes and forms (for example: troops beginning to loot, such as the Cossacks during the surprise attack on Murat, or at Austerlitz where the enemy were hidden, and far closer than expected). The response to these obstacles often decides whether or not the unit will flee. We shall return to this discussion in Section 7.

Although obstacles are bound to appear, the orders issued before battle are integral to victory. Simply looking at the differences in the orders issued at Borodino reflects the difference between good orders and bad ones. Russian orders were simple–to occupy the various points of force; whether they be in fortifications, on high ground, or in positions to ambush.[xxv] In contrast, Napoleon’s orders appear lacking in logic. Although the French appeared to emerge victorious by virtue of holding the battlefield, their losses could not be restored and compared to Napoleon’s earlier battles, we wonder what went wrong. At Austerlitz, there were less than 10,000 French casualties to 36,000 allied; at Friedland, 8,000 French to about 30,000 Russians. The loss of over 30,000 on both sides at Borodino suggests a senseless slaughter. If we look at Napoleon’s orders, we cannot help but question their ‘genius’ alongside Tolstoy, yet we still notice that Tolstoy makes a crucial mistake when analyzing them. According to Tolstoy, ‘this disposition, drawn up quite vaguely and confusedly–if one allows oneself to consider Napoleon’s instructions without religious awe of his genius–contained four points, four instructions. Not one of these instructions was or could be carried out.” (782) In looking at these orders, it is easy to see why Borodino became such a chaotic seesaw deathtrap. Napoleon’s orders were completely unimaginative, they consisted almost entirely in a frontal attack. Napoleon even refused Davout’s request to stage a flanking march and attack around the Russian left.[xxvi] Napoleon’s orders were precisely lacking in the intelligence with which he had won such battles at Austerlitz, in his words to “[be] stronger than the enemy at a certain moment.” (787)

At the same time however, Tolstoy misses the point of these orders, and most general orders. These orders are not strict step-by-step motions that guarantee victory - flabbergasting the issuer when they do not work. These orders are goals during the ensuing battle for officers to target. At Austerlitz for example, these were the Pratzen heights which, despite heavy fighting, were seized by the French, resulting in victory. The provision to make changes to troops dispositions after battle has begun, to adapt to changing circumstances, is also made in these general goals (or Commander’s Intent for the Marine Corps); “after entering combat in this way, orders will be given in accordance with the enemy’s actions…” (783) For once in Napoleon’s battles, Napoleon was not close enough to affect the actions due to his distance from the field. This distance supports Tolstoy’s views that the decisions of a general during battle will make no positive impact; however that is not true in Napoleon’s past career, and it is not entirely true either–for Napoleon did choose not to send the guard in (which could have made a difference). Tolstoy’s argument that ‘it simply could not be done’ is quite unpersuasive. Tolstoy selected this battle to support his views, while opting out of all other conflicts that did not.

The idea that generals and commanding officers have no real purpose once combat has begun is firmly argued by Tolstoy. Yet he gives us multiple examples of that not being true–they each have many purposes that strongly affects the course of the battle–even in the maelstrom of Borodino. On a prefatory note for the next section, in the Face of Battle, John Keegan argues that the role of officers in combat in the 18th and 19th century was to show discipline, cool nerves and shore up morale.

Section 7: The Purpose of Commanding Officers During Combat

Tolstoy argues that the fate of a battle is not decided by officers, but by soldiers–specifically whether they act bravely or if they retreat, spreading panic in the process. A careful analysis of these claims yields a different story. We already saw how officers could decide the fate of a campaign by choosing the most reasonable dispositions at the time and issuing intelligent orders for battle to act as a general plan. In addition to this, Tolstoy provides additional examples of officers taking the fate of battle into their hands; firstly by affecting morale with their orders and decisions, and secondly by taking initiative in order to achieve the general goals of the commanders.

Returning to Prince Andrei’s quote and Tolstoy’s opinion about the power of morale, (see pages 643f) it is notable that officers and commanders constantly aim to directly impact morale during battles by being–as part of their job–“the bold man who shouts ‘Hurrah!’” At Borodino, Kutuzov aggressively tended this morale–upon the supposed capture of Murat, he ‘sent an adjutant to spread this news among the troops.’ When Wolzogen came with bad news, Kutuzov angrily rejected this information, instead accepting Raevsky’s optimistic narrative.[xxvii] Closer to the battle, officers exemplify courage to their men, inspiring them to do their duty. At Schöngraben Prince Bagration led a detachment of Russians in a headlong assault against French troops, he:

“turned around and shouted, ‘Hurrah!’

“Hurra-a-ah!” the prolonged cry spread throughout our line, and… in a disorderly but cheerful wand lively crowd, our men ran down the hill after the disordered French.” (186)

Prince Andrei likewise leads a charge, rallying fleeing troops at Austerlitz (280), and Tushin continuously inspired his battery at Schöngraben–among other possible examples.

As Tolstoy aptly argues, no one can truly know what is to come. Scouting can only generate so much information, and factors change constantly. Officers provide the tactical flexibility to overcome local opposition in major battles. By taking initiative in overcoming obstacles in the attempt to achieve the intent of the general, officers become ‘micro generals,’ where instead of taking on the enemy army (as their commanding officers do), they take on the unit opposite them. The summation of their actions results in the general battle and victory or defeat. For example, we return to Rostov’s charge on page 653. The general orders were to ‘cover the battery,’ and Rostov saw an opportunity to defeat an enemy unit before him. He seized the chance and routed the French–contributing to the overall battle’s balance. Another example comes from the French generals (and Russian generals) leading troops at Borodino. As aforementioned, Napoleon was far away, making the information he received outdated, if not incorrect entirely–while his orders would take so long to put into effect that they were either useless or harmful to the course of events. His generals took the initiative to attempt and achieve the battle plan. When the position of the guns was inadequate, “the nearest commander… moved them forward.” (783) The following two examples are also from Borodino:

“Napoleon’s generals… who were in proximity to the zone of fire and even occasionally rode into it–several times led huge and orderly masses of troops into that zone of fire.” (801)

“All instructions about where and when to move cannon, when to send foot soldiers to shoot, when mounted soldiers to trample the Russian foot–all these instructions were given by the commanders closest to the units, in the ranks without even asking [the generals or Napoleon]. They were not afraid of being punished for non-fulfillment of orders or for unauthorized instructions, because in battle it is a matter of what is dearest to a man–his own life…” (800)[xxviii]

Section 8: Conclusion

Tolstoy is right…. To an extent. Feeling and morale are important. The nerve to stand and fight–to be aggressive in the face of death–is necessary for battles to occur. Those who retreat are thought to lose the battle, and those who retreat do so because their morale gives out. Therefore those with the most morale–those that remain after the others have retreated–have won. But this is a complete explanation. As we have shown through War and Peace, ones feelings are influenced, if not based on, the capacity to reason; or, in other words, feelings have a firm grounding in rationality. Retreating is not a moral failure; men become convinced that the present battle is impossible to fight for a variety of reasons. Likewise, decisions revolving around major events (and the possibility of death is a major event to the individual, as is the fate of a campaign to a general) require a great deal of thought.

Decisions and morale are based on information with the goal being to achieve the most good while minimizing harm. Yet decisions are often made on imperfect information, and reasoning often leads to multiple conclusions. Commanders and men must weigh the possibilities and hope they choose well. However since everything is in flux, that idea may not be correct, whereas another might fit better–but by chance since it is not entirely possible to know what will happen. The difficulties inherent in seeing decisions through, does not mean logic should be thrown out. Morale and ideas are entirely influenced and contingent upon long term and short term factors which altogether affect the ability of men to fight, factors such as positioning, weapons, food, trust in ones leaders, drill, etc. Giving men as much advantage in a fight can make them both more effective and more confident.[xxix]

In War and Peace, Tolstoy’s attempt to understand the psyche of combat resulted in an oversimplified narrative. His argument is inherently flawed and disproved by his own writings. Individuals often do what they are told in the social society of war, follow the hierarchy of command, and attempt to do their duty to the best of their abilities. Each part of society has a role to play, the soldier, the officer, and the general. They are all intertwined and victory is contingent upon their functioning together.

Works Cited

Harvey, Robert. The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

McPeak, Rick and Orwin, Orwin Tussing. Tolstoy on War: Narrative Art and Historical Truth in “War and Peace.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, 2012.

Pevear, Richard and Volokhonksy, Larissa, trans. War and Peace of Leo Tolstoy. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

Footnotes

[i] For additional supporting evidence of morale as the only important factor in deciding the fate of an action, see the following: Richard Pevear and Volokhonksy, Larissa Volokhonksy trans. War and Peace of Leo Tolstoy (New York: Vintage Books, 2007), 190-1, 279, 643-4. [ii] Tolstoy, 742 [iii] Another example of Kutuzov making a rational decision based on the many proposed ones is during the Russian retreat after the Austrian tragedy of the Ulm on page 170. [iv] For Prince Andrei, at Austerlitz this passage refers to his picking up the flag and rushing at the French lines–despite the death about him. (280) Prince Andrei likewise has a disregard for death at Borodino when he stoically watches the shell landing and reprimanding the un-noble conduct of his officers (811). For the regimental commander, his focus on his duty as an officer likewise prompts him to totally ignore the possibility of death to try an rally his men. (190) [v] Tolstoy, 256. [vi] Tolstoy, 608-9. [vii] Russian soldiers have a simple desire which is aligned with the general goals of the Russian commanders. Tolstoy, 1093. [viii] At Schöngraben alone, there are examples of both of these happening: Dolokhov displaying his valor to his commanding officer–who can ensure his promotion, and the two generals arguing with one another. [ix] The only man with more authority than Kutuzov is the Tsar. However he cannot be competed with. Like Kutuzov, the Tsar’s goals are aligned to the goals of the campaign. [x] Such as the battles of Vyazma, Krasnoi, Polotsk and Berezina. [xi] The moments when he is not convinced and still must follow his subordinates are when the Tsar overrules Kutuzov, such as at Austerlitz. Kutuzov nevertheless performs his duty to the best of his abilities. [xii] Tolstoy, 186. [xiii] The purpose, as Andrei notes during the military discussions at Drissa on 634 is to achieve the goals of the campaign. There are many paths to victory, perhaps Benningsen would have been an excellent commander in chief as well–he proved capable during the subsequent invasion of Europe. Thus these people do not seek to undermine the campaign but to achieve the goals with their own ideas based on their own experience and reason. [xiv] For a discussion of the positions of the French and Russians, see Robert Harvey, The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815 (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 482-487 [xv] Tolstoy, 756, 768. [xvi] Harvey, 781 [xvii] We do not feel the need to expand more fully upon this topic since it is simple common sense, proven throughout history, that defensive positions–usually elevated positions–provide a defensive advantage to the defender: for example Alesia (52 BC) or Badajoz (1812 AD). [xviii] He would have seen if the infantry which proceeded to attack his Hussars following his attack were far away, giving him time enough to charge. [xix] The battle of Islawanda is an exception to this for its own specific factors. However given the proportionality of complete massacres to the few exceptions–it is quite clear that having but bayonets and knives against numerous cannon and rifles tends to be a death sentence. Figure 1: La carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l'armée française dans la campagne de Russie 1812-1813

[xx] “…a change took place in the relative strength of the two armies (in spirit and number), as a result of which the advantage of strength turned out to be on the Russian side. Though the position of the French troops and their number were unkown to the Russians, as soon as the relations changed, the necessity of attacking expressed itself at once in a countless number of signs. These signs were:… the abundance of provisions in Tarutino, the information coming from all sides about the inactivity and disorder of the French, the replenishing of our regiments with recruits, the good weather, the prolonged rest of the Russian soldiers….” (991) [xxi] For example, say some soldiers are not fed enough food. They will likely not be able to build fortifications effectively since they don’t have enough calories to work hard and quickly. They will therefore not be in as good a position, beyond still not being fed, if the enemy were to attack these unfinished positions. Being hungry is never good for morale, as is being unsure of ones defensive position (safety). [xxii] As the reader will note, the following passage also reflects, once more, the importance of position–as well as numbers and communication: “Kutuzov received information… that placed the army he commanded in an almost hopeless position. The scout had reported that the French in enormous force, having crossed the bridge in Vienna, were heading towards Kutuzov’s line of communications with the troops coming from Russia. If Kutuzov decided to stay in Krems, the one-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-man army of Napoleon would cut him off from all communications, surround his exhausted forty-thousand-man army, and he would find himself in the position of Mack at Ulm. If Kutuzov decided to abandon the road leading to communications with the troops from Russia, he would have to enter with no road into the unknown territory of the Bohemian mountains, defending himself from the superior numbers of the enemy, and abandoning any hopes of communication with Buxhöwden. If Kutuzov decided to retreat down the road from Krems to Olmütz to unite with the troops from Russia, he would risk being forestalled on that road by the French, who had crossed the bridge in Vienna, and thus being forced to accept battle on the march, with all his heavy baggage and transport, and to deal with an enemy that outnumbered him three to one and surrounded him on both sides. Kutuzov chose this last course.” Tolstoy, 170. [xxiii] Tolstoy, 990, 1985-7. [xxiv] Even before this march, Napoleon’s orders in Moscow appear contradictory and without purpose. He attempts to ‘rule’ Moscow as if there were still inhabitants, althewhile allowing his troops to go about looting unproductively in Moscow: “Napoleon prescribed to all his troops that they take turns going around Moscow a la maraude…” (1004) All orders somewhat contradicted each other and achieved naught but time and resources wasted. The passage of orders issued in Moscow appears on 1002-1005. [xxv] Tolstoy, 768. Harvey, 781. [xxvi] Harvey, 781. [xxvii] Tolstoy, 807. Bagration acts the same way as Kutuzov at Schöngraben, where his presence “accomplished a very great deal. Commanders who rode up to Prince Bagration with troubled faces became calm, soldiers and officers greeted him merrily and became more animated in his presence, and obviously showed off their courage before him. (183)” [xxviii] Another example is at Schöngraben where Tushin’s guns were incredibly effective at destroying French assets and slowing down to French army without any orders (such as on page 181). [xxix] Imagine–to create an image which reflects our arguments–a 14 year old who has never stepped out of his house and plays no sports being told fight an Olympic wrestler. Even if the teenager is 100% committed and feels that he can win, there is almost no possibility whatsoever that he will win against the wrestler–even should the latter not be completely committed to the fight.

Comments