Birds and Risk

- Nathan Decety

- Apr 7, 2020

- 3 min read

Summary: risk aversion in birds highlights the importance of risk with unknown parameters.

I was sitting on a bench in a park (across from the villa Borghese in Rome). I dropped a fat wad of the pastry I was munching on. It landed right by my foot. Suddenly, a small bird swooped over and grabbed about half of the food, and flew a couple of meters away. First of all, hats off to the ballsy bird. Second, this created a very interesting experiment because all local birds now had a “all else being equal” situation. The two pieces of pastry available were both somewhat sizeable,[1] but one was being eaten by a little bird (Piece 2), while the other was still by my foot (Piece 1).

Both had some barrier to entry of sorts, identified here as risk: the piece by my foot carried the risk that I was potentially crazy while the piece eaten by the little bird meant that any newcomers might face a fight.

The difference was that the risk of me losing my mind and trying to crush the birds with my foot was unknown, while the competition from the little bird was known, and it was not very big. Of course I am not insane and the actual risk from me was negligible (if not negative – I might have dropped more pastry for my new friends to enjoy). Research has shown that the birds will go for food that is most available at the lowest expenditure of energy: if you placed a bunch of crumbs over a large area or a slightly smaller amount of crumbs but over a smaller area, they will go for the ones that are most concentrated.

The result? All the birds went straight for the piece eaten by the brave little bird. Over time, the more birds came in to chomp away the piece (Piece 2) stolen by the little bird, the less food was available. And yet more kept on coming! The individual pieces being eaten by all, including the little bird, were smaller and smaller. Competition reduced the pastry per capita to nearly nothing, and the initial efforts of the little bird were only salient and worthwhile for a few crucial moments.

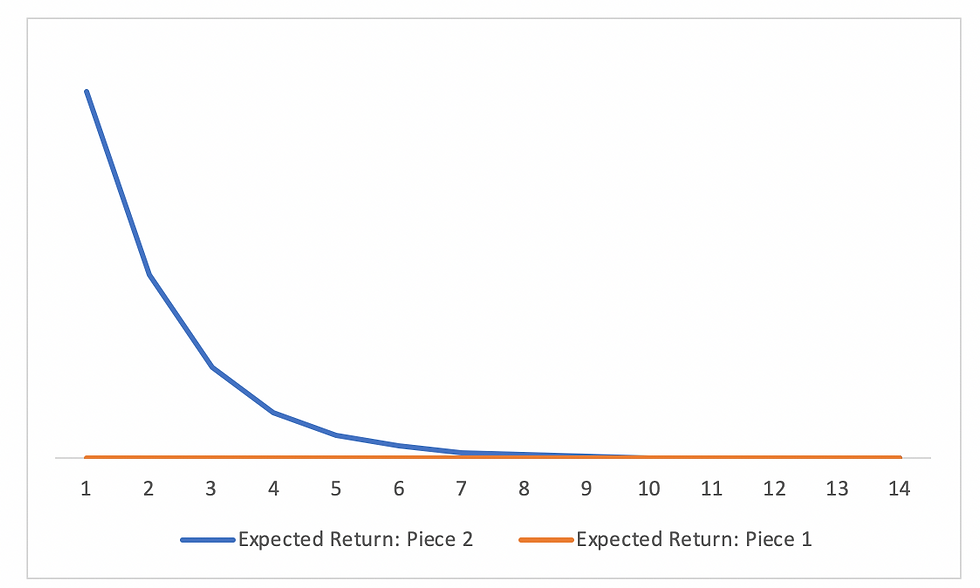

If we graph the return over time of choosing where to go for food, it would look somewhat like this:

On the X Axis are the numbers of birds eating Piece 2. Each time another bird comes in, the total available per bird diminishes. The competition remains essentially the same however because the piece a new bird wants to steal is only being eaten by one bird, not all of them at the same time. However a better view of the decision might be to multiply the return times the risk, which would look something like this:

Since the risk is unknown, the potential return looks extremely poor, and the birds will only come and finesse the piece of pastry by my foot if there is no other option at all in their current context. Birds of course need to continuously consume calories because they cannot store fat (otherwise they would be too heavy to fly), and they expend enormous amounts of calories flying.

However, if for some reason the risk was seen as less – i.e. by years of evolution where they felt that humans were not dangerous, or that only a few key moments of observation of my behavior was necessary to determine that I was not dangerous – perhaps an equally sizable horde of birds would have gathered on the piece by my foot (Piece 1).

Takeaways: not knowing much information should multiple available risk enormously. Assuming a small amount of information is enough information can be deadly. Lack of knowledge is not only correlated with risk, it is in fact congruent with risk.[2] In a competitive environment winners are only winners for a short amount of time.

[1] The piece next to my foot was actually a little larger. [2] Take for example the Covid-19 pandemic. Available data could be inconsistent with actual viral epidemiological outcomes, not only other viruses but also the – most likely – tampered data provided by the Chinese government. When we do not know what it could mean, the future becomes a great possible vacuum of risk.

Comments