The Liberalizing Curse: Negative Impacts of Integrating Emerging Economies’ Capital Markets

- Nathan Decety

- Sep 6, 2022

- 23 min read

If a foreigner were to give a European Middle Age noble thousands of pounds of gold, can the noble really be expected to improve the economy they manage, or will they use it to purchase luxuries and fund a military expedition against a rival? This may be a strange way to open a paper about investing in emerging markets, except that many of the rich and powerful in developing countries essentially act like nobles. Inequality in many developing countries today is similar to inequality in the early European Middle Ages,[1] and nobles in the Middle Ages extracted resources out of their economies just like local emerging market elites – who do so to fund their lifestyles and to accrue power.[2] In this piece we argue that because of the extractive nature of emerging market sociopolitical structures, integrating financial markets have increased the relative power of elites in those societies without setting the stage for long term improvements in their fundamental economies. Continued volatility and short-term trading patterns can be expected to continue. In other words, granting local elites more power should not be expected to lead to any positive liberalizing changes in the future.

Let us first discuss the purpose of capital markets. According to the St. Louis Fed, “Capital markets allow traders to buy and sell stocks and bonds, and enable businesses to raise financial capital to grow. Businesses also have reduced risk and expenses in acquiring financial capital because they have reliable markets where they can obtain funding.”[3] Why is it important for businesses to grow? Because they provide goods and services desired by people. Growth should be reflected in improvements in quality of life for individuals. Improvements in median income per capita is therefore generally a good representation of how much people have benefited from economic growth.[4] Economic growth is also positively correlated with happiness in most countries.[5] Thus, improvements in the lots of individuals should be the benchmark of success.

How does integrating capital markets fit into this picture? Theory suggests integrating capital markets is beneficial because it increases stock market correlation with world markets, reduces required dividend yields, and improves credit ratings.[6] As such, cost of capital for companies are decreased and economic growth is stimulated.[7] This is reasonable if capital went to organizations that delivered required services, paid for local labor, and made local investments. Tapping into deeper liquidity would allow these companies and organizations to undertake greater projects at cheaper rates. The theory is reflected in major institutional perspectives on emerging market economic and stock market growth.

Back in the 1990’s and 2000’s, there was a feeling that emerging markets were on the cusp of greatness. In 1995 for instance, a World Bank Report stated “growth in developing country stock markets will be enhanced as policies liberalizing trade and investment regulations, realigning exchange rates, consolidating public finances, and continuing with privatization are implemented.”[8] Other institutional groups focused on individual countries – in particular China – exemplified by Goldman Sach’s famous BRIC article.[9] The theme that emerging markets can grow much faster than their developed counterparts, and that this growth will be magnified the moment they adopt more liberal economic policies has continued to be expounded.[10] The key point missing from these institutional perspectives is that truly liberal economic policies are quite difficult to implement, and that macroeconomic and political instability are endemic in emerging economies.

In the following section, we will first discuss the nature of returns in integrated emerging markets and who has benefited from them. Then we will look at developing country economic data associated with these emerging markets to note if the livelihoods of people have improved over the period. Third, given the impacts emerging markets have had, we will discuss implications on future economic growth and conditions in developed countries. We use a rather loose definition for emerging market economies based on a combination of MSCI’s Emerging Markets, Frontier Markets and Standalone Market Indices.[11] Our reason for doing so is that we wish to broadly discuss integrating developing markets in the global financial system.

Integrated Emerging Market Behavior

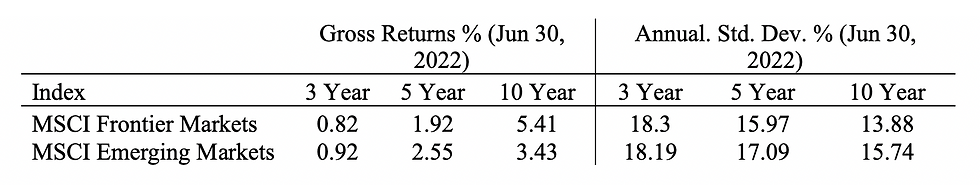

Though emerging market economies have indeed grown over the last several decades, their security markets have been exceedingly volatile and delivered paltry returns. Consider the following comparable data from one of the latest Index Factsheets from MSCI:[12]

MSCI notes that $100 invested in June 2007 would be worth $97.92 or $87.22 by June 2022 if it had been invested in Frontier or Emerging Markets, respectively. A longer time frame of November 2002 to June 2022 maintains the same pattern of 6.68% gross returns for Frontier Markets and 9.25% for Emerging Markets. Expanding the time frame even more does not help. The total annualized return for a long-term buy and hold of the MSCI EM Equity Index from 1993-2020 was 4.7% with a standard deviation of 22.3%, and a maximum drawdown of 61% - which compares unfavorably to a simple buy and hold of the same time-period of the S&P500 which yielded annualized returns of 9.5%, a standard deviation of 14.8% and a maximum drawdown of 51%. The same pattern holds for other securities such as national and corporate debt. Investors have better buy and hold returns in developed markets, with far less risk.

Financial advisers repeat over and over that one should invest for the long run – that the vicissitudes of the market will work themselves out and leave the investor better off than before.[13] While this advice may historically have been true for developed markets, the vicissitudes and low returns render this advice misplaced with regards to emerging markets. Instead, thoughtfully entering emerging markets post their frequent crises and holding for relatively short-term periods of time would be the optimal strategy – yielding excellent returns.[14]

The high volatility and low returns from emerging markets is due to a combination of structural and liquidity shortcomings. Focusing on the former, there are three particularly salient risk factors associated with emerging markets that are generally less present in developed markets, which are discussed by every professional investment vehicle. Take for instance Ameriprise’s, “Political risk: Emerging markets may have unstable, even volatile, governments. Political unrest can cause serious consequences to the economy and investors. Economic risk: These markets may often suffer from insufficient labor and raw materials, high inflation or deflation, unregulated markets and unsound monetary policies. Currency risk: The value of emerging market currencies compared to the dollar can be extremely volatile. Any investment gains can be potentially lessened if a currency is devalued or drops significantly.”[15] We may add to Ameriprise’s list commodity risk, for emerging markets are historically extractive economies selling commodities to other countries. As the World Bank writes in 2022, after decades of development & opportunities to diversify, “Commodities are critical sources of export and fiscal revenues for almost two-thirds of EMDEs [emerging market developing economies] and three-quarters of low-income countries. More than half of the world’s poor reside in commodity-exporting EMDEs. Countries whose exports are heavily concentrated in one or a few commodities tend to experience high volatility in their terms of trade and output growth.”[16] Hundreds of years of data shows that commodity prices fluctuate quickly and in great magnitudes, capital flows surge and decline rapidly, and unexpected global political conditions heavily impact commodity markets.[17] Commodity-based economies are fragile and exposed to the vicissitudes of fickle global demand.

Generally, when risks are resolved, valuations increase. But considering that risk factors tend not to change, what drives changes in emerging market valuations are flows of investments rather than improvements in underlying worth; returns are caused by good liquidity conditions in rich countries and investors’ hunt for yield, which drive traders to make emerging markets bets. Stories of economic realignment and phenomenal future growth are shared to increase excitement. The investments that pour into emerging markets do help companies grow in emerging markets, but it is the investment that causes growth, and not growth that attracts investment.[18] Inevitably therefore, when conditions change, as they are bound to because of the aforementioned risks, or if liquidity conditions change in developed countries, investments are pulled out.[19] Even before the 1997 emerging market crisis, economists warned, “large capital inflows can also have less desirable macroeconomic effects, including rapid monetary expansion, inflationary pressures, real exchange rate appreciation, and widening current account deficits… history has shown that the global factors affecting foreign investment tend to have an important cyclical component, which has given rise to repeated booms and busts in capital inflows.”[20] In short, structural problems incentivize traders to make speculative short-term bets that can be very profitable.

Short-term traders seeking returns are not the only ones to benefit massively from integrated emerging markets, local elites earn enormous sums from liberalizing. Equity prices tend to rise by 3.3% per month over an 8-month window preceding implementation of stock market liberalization.[21] Following integration, equity continues to become more valuable, as research finds the cost of capital lowered by 11 basis points per year measured by dividend yields and lower expected stock returns of 4.5% per year (implying higher present prices).[22] Increased value would be fine if ownership was distributed across a society, but in developing markets ownership of firms is extremely concentrated among the wealthy – particularly within single wealthy families.[23] Furthermore, research shows that improvements in valuations in emerging markets after liberalization often stem from additional share price issuance, which again benefits local elites.[24]Or, as Das and Mohapatra write about the impact of market integration, “we find a pattern indicating that income share growth accrued almost wholly to the top quintile of the income distribution at the expense of a “middle class…” A surprising finding is that the lowest income share remained effectively unchanged in the event of liberalization.”[25] As a result integrating financial markets yields much higher security prices which directly enrich the well-off local elites. Resource inequality is therefore exacerbated, which is reflected in Gini coefficients as well as wealth & income inequality, all of which tends to be worse in the developing world than in the developed world.[26]

Let us pause briefly to note what we have discussed. Integrated emerging markets are highly volatile and present opportunities for short-term trading, and integrating emerging markets is very lucrative for wealthy local elites who already owned the assets being bought and sold globally. We now turn to historical changes in economic conditions in developing countries to touch on growth connected to emerging market integration.

______

Developing Economies’ Economic Improvement

Integrating financial markets should have beneficial effects on underlying economies, we note the economic performance of developing countries and regions. To give credit where credit is due, over the last several decades, global poverty has been greatly reduced, and emerging economies are growing. Research suggests that developing economies will continue to grow faster than developed ones at uneven paces.[27] As economies grow, it is reasonable to expect the people working within to be better off, which generally has occurred.

Using the Penn World Table database,[28] which estimates GDP per capita and adjusts for differences in the costs of living between countries and for inflation, we calculate the compound average growth rate between 1970 and 2019 for developing and developed countries. Where data was lacking from 1970, we used 1990 as the starting point. As mentioned at the beginning of this piece, developing countries are defined as all listed countries under MSCI’s emerging, frontier, and standalone market indices.[29] The resulting growth rates are the following:

Though there is a difference in growth rates between developing and developed countries, providing substance to the idea that developing economies will catch up to developed ones, the difference is slightly muted considering just how low GDP per capita in developing economies was decades ago. Furthermore, not all countries in the developing world have grown at the same rate – after a century of growth, only some countries – particularly in South and East Asia – have begun closing their gaps with the developed world.[30] Economic conditions also do not change in a linear pattern. In the 1960’s and 70’s, emerging economies enjoyed rapid growth. During the 1980’s and early 1990’s, that growth decreased to nearly nothing in what is commonly described as a lost decade. The late 90’s through 2010’s were once again good – in part because of massive foreign investment – and despite various crises.

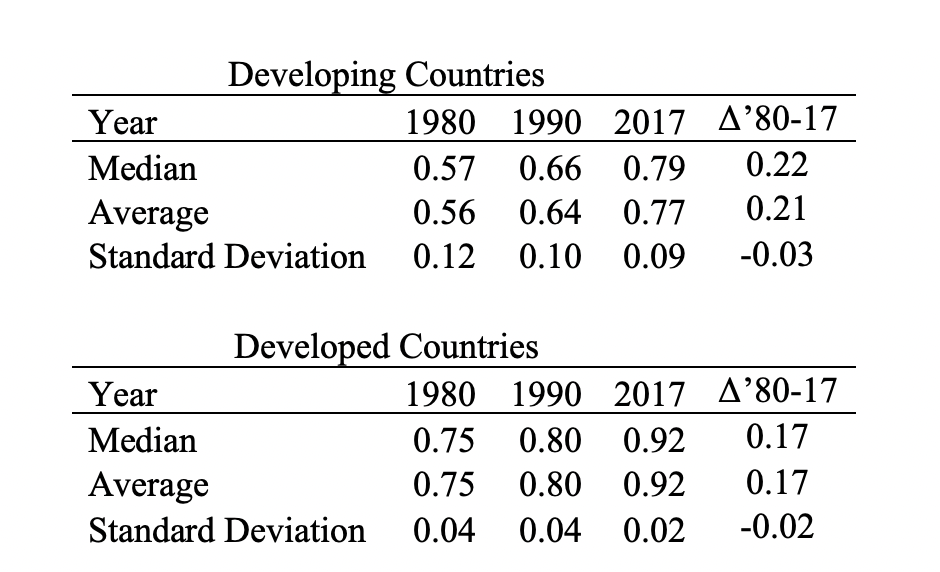

A different perspective on the same target of studying people’s lots is changes in the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Index which includes proxies for standards of living, access to education, and long healthy lives.

The pattern is the same as previously noted – developing countries have certainly improved overall, but have done so unevenly, as suggested by the higher standard deviation of HDI scores.[31] A more complex and thorough metric – the World Economic Forum’s Social Mobility Index – echoes similar evidence of inequality and development.[32]

While developing countries have grown economically, and this growth has been beneficial to their populations, it has not benefited all equally. Emerging economies have more income inequality than the most unequal OECD countries, as noted in the previous section.[33] Even though some emerging market countries have reduced income inequality over the last several decades, the majority have actually become more unequal.[34] In summary, growth in developing countries has overall been good, and while market integration helped enable some economic growth that percolated down to most individuals – as denoted by changes in real GDP per capita and HDI scores – the main beneficiaries of economic growth and integration were the wealthy. The final piece of this essay will focus on the implications of some of the points that have been made thus far and discuss the future prospects of emerging market economies.

_____

Future of Developing Economies with Integrated Markets

In 2022, the Economist – echoed by other news sources & institutional groups warned that emerging markets face major headwinds consisting of higher interest rates, difficult geopolitics, high inflation, and may therefore be on the verge of a lost decade once more.[35] After decades of development and investment, emerging markets are still exposed to similar risks as before. Why? Although there are a plethora of reasons, I will focus on the implications of the aforementioned volatile nature and elite enrichment associated with integrated financial markets. I intend to argue that emerging markets are trapped in a cycle of volatility and subjugation to their elite ruling classes, and that integrated financial markets enable this cycle.

The first point to address is volatile capital flows which in turn contribute to the volatility of emerging markets and their foreign-currency dependent economies. Considering that one of the main causes of volatility are major risks in the underlying economy, one should reasonably expect volatility in capital flows to dim if the economy being invested in becomes worthier of longer-term investments; investors with exposure to risk factors that are resolved earn generous returns. In other words, traders will continue to invest with short term horizons, to “ride the wave,” unless conditions change.

The second point to address, to which the rest of this essay will be focused on, are the negative implications of elite enrichment on the economy – which generates the conditions to which traders respond. We make take as a given that enriching a certain person, in an economy where that money may be employed for nearly any purpose desired, will make that person more powerful. Thus, enriching local elites without enriching the other portions of society mean elites have accrued additional power.

In their groundbreaking work Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson discuss how countries escape poverty when they establish appropriate economic institutions and commensurate pluralistic political systems. They split human societies into two types based on their politico-economic institutions: extractive or inclusive. In their words: “Countries differ in their economic success because of their different institutions, the rules influencing how the economy works, and the incentives that motivate people… Inclusive economic institutions, such as those that allow and encourage participation by the great mass of people in economic activities that makes best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish. To be inclusive, economic institutions must feature secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract.”[36] To further explain Acemoglu and Robinson’s point, we need to point out that three factors drive economic growth – accumulating capital stock, increasing labor inputs (i.e. number of hours worked, number of workers, productivity), or technological advancement. Over the long run however, it is technological breakthroughs that enable growth.[37] Innovations, in turn, tend to be ‘pushed on to the market from the supply side,’ and come in major technological waves.[38] Enabling technological breakthroughs is typically dependent on either focused, organized, governmental intervention – yielding specific technologies that must be repurposed by other creative organizations – or by enabling creative people to experiment and almost randomly come up with ideas that change the world.[39] In order for people to develop and share their ideas, they should be supported with resources and education and must be allowed to think critically, which is provided by inclusive institutions.

In contrast, “Extractive political institutions concentrate power in the hands of a narrow elite and place few constraints on the exercise of this power. Economic institutions are then often structured by this elite to extract resources from the rest of societies.”[40] In sum, inclusive institutions result in more general and sustained prosperity and exclusive institutions yield little sustainable economic growth. Or, in Tom Palmer’s words, “I spend much of my time in countries with weak rule of law and lots of state interventionism and, consequently, with both low average incomes and huge gaps between the powerful and the rest of the population. In those countries, it’s often the case that those with the greatest wealth acquired it, not be creating value for others, but by getting special favors from their friends in the state apparatus, by taking bread from the poor in the form of subsidies, and generally by being scoundrels.”[41]

The status of emerging countries as ‘extractive economies,’ per Acemoglu and Robinson’s definition, can be derived from several metrics including inclusive political regimes with democratic systems, scale of corruption and crony capitalism, and societal education. These factors tend to be correlated with one another – for instance countries with high investments in education are more democratic, have higher HDI scores, and lower rates of corruption.[42]

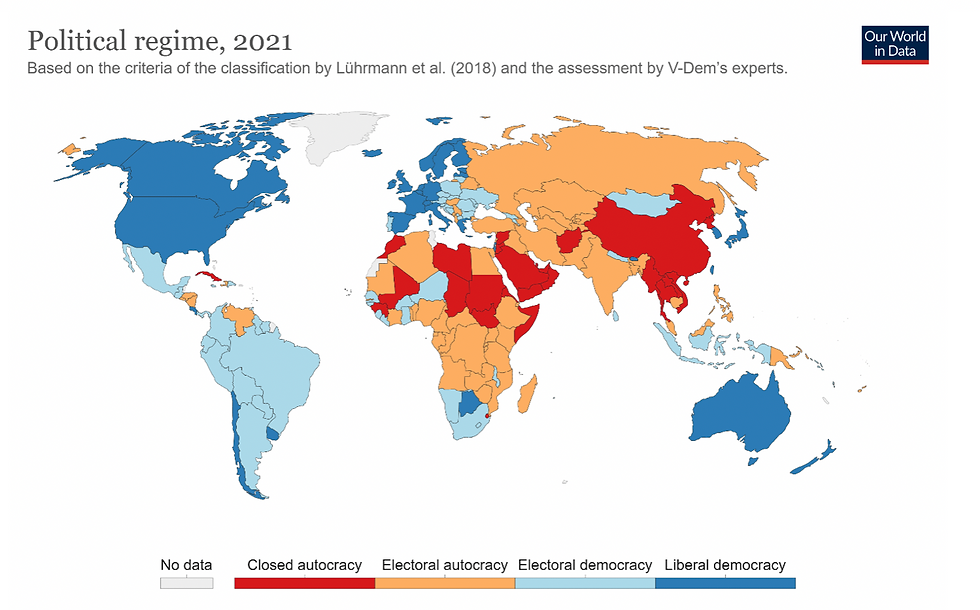

By any metric, nearly none of the developing world is an open democracy. In fact, the majority of the developing world has barely changed its political system over the last 30 years. In these political systems, elites wield their wealth with complete or near impunity and utilize the state to support and enhance their positions. One notes in the map below that most developing markets are generally classified as autocratic.

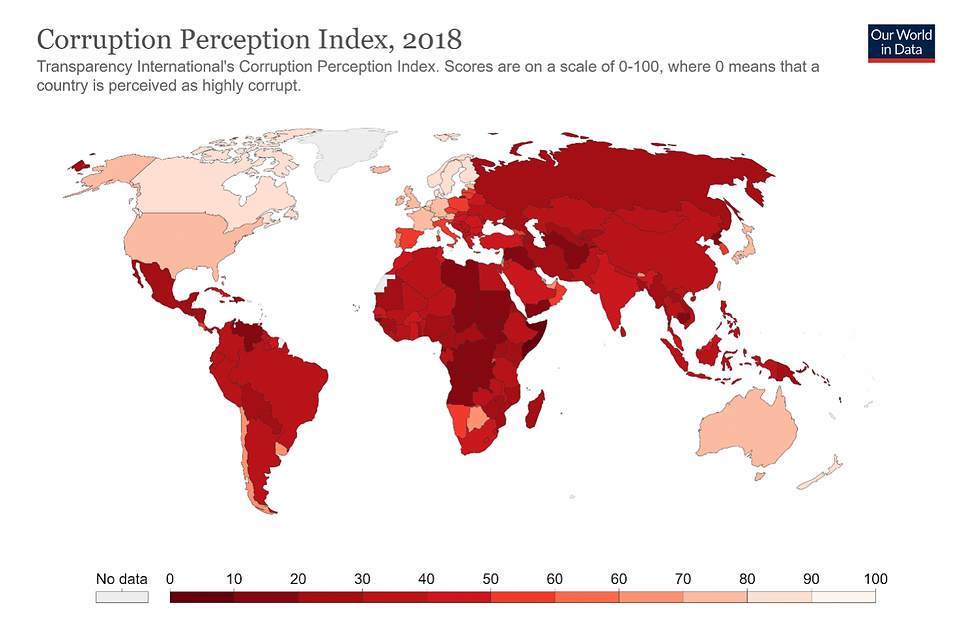

Rampant corruption across much of the developing world – both among the rich and poor – is reflected in corruption indicators, which suggest a bleak state that does not tend to improve.[43]Alone, corruption is a drag on economic growth and on communal trust. When considering that corruption is shared by elites – who see the processes of the state as a means of enrichment, it is a long-term societal curse. The results shown below for the Corruption Perception Index are replicated across other corruption measurements, such as the IMF’s ‘Sentiment-Enhanced Corruption Perception Index,’ and the Economist’s Crony Capitalism Index.[44] The result of crony capitalism and corruption is also reflected in large income and wealth inequality in developing countries, as previously noted.

Ameliorating economic and political conditions is possible through education: education enables innovation, reduces rates of societal corruption, and provides countless positive externalities. While indices reflecting the rate of education across the developing world have been showing positive trends, a greater problem exists in the form that education is taught in; unfortunately, across much of the developing world, critical thinking is not sought after.[45] A humorous representation can be taken from Nobel Prize Winner Richard Feynman’s biography, in which he discusses the quality of education in Brazil:

‘…I attended a lecture at the engineering school. The lecture went like this, translated into English: "Two bodies, are considered equivalent, if equal torques, will produce equal acceleration."

The students were all sitting there taking dictation, and when the professor repeated the sentence, they checked it to make sure they wrote it down all right. Then they wrote down the next sentence, and on and on. I was the only one who knew the professor was talking about objects with the same moment of inertia, and it was hard to figure out. I didn't see how they were going to learn anything from that. Here he was talking about moments of inertia, but there was no discussion about how hard it is to push a door open when you put heavy weights on the outside, compared to when you put them near the hinge - nothing! After the lecture, I talked to a student:

"You take all those notes - what do you do with them?"

"Oh, we study them," he says. "We'll have an exam."

"What will the exam be like?"

"Very easy. I can tell you now one of the questions." He looks at his notebook and says, "'When are two bodies equivalent?' And the answer is, 'Two bodies are considered equivalent if equal torques will produce equal acceleration.'"

So, you see, they could pass the examinations, and "learn" all this stuff, and not know anything at all, except what they had memorized.’[46]

Other germane perspectives on weak educational systems abound. School rankings [admittedly biased] very rarely feature schools outside the developed West or highly developed East Asian countries like Japan and China. Talented students with means tend to travel to elite western institutions to further their education. The output of quality schools is either good practitioners & teachers, or high-quality research. The Global South (developing countries) is overwhelmingly out-published by the Global North (developed countries), even when it comes to studies that focus on the Global South.[47]

I’ve made the case that – based on restrictive governments, levels of corruption, and available education opportunities, the majority of developing countries can be classified as extractive. Since we are discussing future long-term growth in emerging markets, their status as extractive economies is poignant: in extractive economies, elites are extremely wary of innovation and education because anything can potentially threaten their power. Elites are not incentivized to enable growth because innovation challenges their control and could endanger their position in the social hierarchy. Thus, when institutions like the World Bank discuss future development in emerging markets if they only would enact liberalizing legislature, they are essentially making prescriptive recommendations rather than forecasts.

An output of developing countries as extractive economies is their continued dependency on global commodity markets as economies are not enabled to diversify. The UN defines a country as dependent on commodities when commodities account for more than 60% of its total merchandise exports in value terms. In 2019, the UN noted that “67% of developing countries (91 out of 135 countries) are dependent on commodities, a situation that has changed little in the last two decades. Least developed countries are even more dependent, as more than 80% of their export earnings come from commodities.” If the situation has changed little in the last two decades, it means the situation has in fact changed little since decolonization or de-facto de-imperialism, for most developing countries were integrated into empires and turned into export-oriented centers of commodity production.

A few current-day case studies may drive home the points being made above. Ghana takes in the majority of its revenue from commodity exports and barely taxes its population – government spending is typically aimed at securing reelection. Ghana is on the verge of asking for its 17nd IMF bailout.[48] Iraq has been without an effective government for about a year, the government is funded by energy sales on the global market, and the country has been in and out of conflict since its previous dictator was killed as a result of the second Gulf War; Iraq’s political problem is due to “politicians who see control of the state as a zero-sum scramble for patronage and wealth…”[49] Sri Lanka defaulted on its sovereign debt in May 2022, its economy having suffered from decades of theft by the erstwhile ruling Rajapaksa dynasty.[50]

These cases reflect one of the key points made by Carmen and Reinhoff in This Time is Different, Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, that emerging markets perennially default and lurch from crisis to crisis.[51] This same volatility in turn contributes to make major political switches so attractive as people yearn for a solution, for organization & stability out of chaos.[52] The problem of course is that running a government takes long, slow, difficult, and often unrewarding work; drastic swings towards socialism or autocracy do not fix underlying societal or economic issues, it only tends to replace the ruling social class with a different set of peoples.[53] Finally, consider that since control of the state is connected with status and wealth, anyone with ambition will seek to take control of the state. If there is no limit over how to block individuals for taking the state – if repression and violence is used to block others from rising – then violence is a necessary, tool to take control of the state. In other words, political violence may be necessary for ambitious individuals to rise, just like in the Middle Ages.

A subpoint should be addressed because some emerging economies have done well despite being relatively extractive, in particular China. When a solution is known and understandable, a well-organized autocratic government may be effective at enabling said solution. [54] The problem is that autocratic regimes may not have clear goals that are beneficial to their populations (i.e. they might desire expansion through war), or their need to maintain an autocratic regime may require them to brutally suppress their populations. However, China, as a one-party state edging closer to fascist principles in practice while maintaining communist principles in theory has been able to significantly improve the lot of its population. That said, it remains to be seen whether growth will continue, as pre-identified catchup growth solutions are exhausted, and creativity and innovation are checked by the one-party state. Chinese Nationalism stoked by the communist party may also draw China into a destructive war over Taiwan or with India; should China undergo a Sino-Soviet style fallout with Russia, a conflict over Manchuria may ensue. The other country that has recently chosen to follow a well-organized and modern take on fascism is Russia, which provides an opposite example to China’s recent – generally economically positive – past. Unlike China, Russia’s growth is largely dependent on commodity markets, particularly global oil and gas markets.[55] It has used its income to invade its neighbors and support autocratic regimes across the world. Following its conventional military invasion of Ukraine in 2022, its economy is expected to shrink due to a brain drain and aggressive sanctions.[56] In both Russia and China’s case however, both countries have long histories of organized governmental control that many developing countries lack – making autocratic rule in other developing countries more a continuation of chaos and wealth extraction than a threat to global stability.

Continued growth and development of emerging countries will be hampered by their status as extractive economies; volatility is expected to continue, exacerbated by western traders and fluctuating commodity markets. Returning to the effect of integrating emerging markets – since the integration has principally rewarded the rich, it is not a big jump to point out that increasing the wealth of the powerful further will continue to entrench them as the wielders of power in their country, thus exacerbating the extractive economic conditions developing countries find themselves in.

In a sense, that many of these countries claim they are liberalizing to enable economic growth could be seen as gaslighting. Some liberal policies create short term mutual coincidences of wants: integrating the market is a good economic policy for emerging market economies as well as a means of elite enrichment. The problem we wish to note is that further policy enactments in favor of economic growth may require elites to cut down their rent-seeking inclinations. Assuming that humans tend to act in their perceived short-term interests, the probability that these further policies may be pursued is low. In other words, it is foolish to see some liberalizing moves from the past as the start of a generally positive process, there is no growing momentum. Instead, those seemingly liberal policies will exacerbate the oppressive conditions under which so much of humanity lives.

Conclusion

Integrating emerging markets into global financial markets has enabled local elites to boost their power, stunting their economies by chaining them to commodity production, blocking innovation and diversification, and providing volatile environments for traders to make speculative trades – exacerbating market and economic volatility. While integrating these markets may have contributed to economic growth in the short term, it has also enabled the status quo to continue.

[1] Guido Alfani, “Economic inequality in preindustrial times: Europe and beyond,” Journal of Economic Literature Vol. 59, No. 1, (2021), pp. 3-44 [2] Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer, “Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolutions,” 1992, pp. 8. [3] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Understanding Capital Markets,” https://www.stlouisfed.org/education/tools-for-enhancing-the-stock-market-game-invest-it-forward/episode-1-understanding-capital-markets#:~:text=Capital%20markets%20allow%20traders%20to,where%20they%20can%20obtain%20funding., Accessed August 3, 2022. [4] Max Roser, “What is economic growth? And why is it so important?” Our World in Data, Updated March 13, 2021 https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-economic-growth, Accessed August 4, 2022. [5] Neha Kumari, Naresh Chandra Sahu, Dukhabandhu Sahoo, Pushp Kumar, “Impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness: Evidence from emerging market economies,” Journal of Public Affairs (2021). [6] Geert Bekaert, Campbell R. Harvey & Robin L. Lumsdaine, “Dating the Integration of World Equity Markets,” NBER Working Paper No. 6724 (1998) [7] Henry, Stock Market Liberalization, Economic Reform, and Emerging Market EquityPrices, Published by the Journal of Finance, Vol. 55 No. 2 (2000), pp. 529-564. [8] The World Bank, “Trends in developing economies – 1995,” July 31, 1995 [9] Jim O’Neill, “Building Better Global Economic BRICs,” Goldman Sachs, November 2001, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/archive/archive-pdfs/build-better-brics.pdf [10] See for instance, Peter Muldowney, “Tapping the Growth Opportunity of Emerging Markets,” Strategic Exchange of CCL Group, https://www.cclgroup.com/docs/default-source/en/en-strategic-exchange/tapping-the-growth-opportunity-of-emerging-markets.pdf?sfvrsn=403a25c8_10 [11] See MSCI, “MSCI Global Market Accessibility Review,” June 2022, https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/8ae816b1-fa03-bae3-0bb4-1a3b2bf387bf?t=1656972645260 [12] MSCI, “MSCI Frontier Markets Index (USD) Factsheet,” July 2022, https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/f9354b32-04ac-4c7e-b76e-460848afe026 [13] See for instance, Nick Murray, Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth: How You and Your Financial Advisor Can Grow Your Fortune in Stock Mutual Funds (Nick Murray Company, Inc, 1999). [14] William N. Goetzmann & Dasol Kim, “Negative Bubbles: What Happens After a Crash,” European Financial Management, Vol. 24 (2), pages 171-191. [15] “Investing in emerging markets,” Ameriprise Financial, https://www.ameriprise.com/financial-goals-priorities/investing/emerging-market-investments, accessed August 20, 2022. [16] Garima Vasishtha, “Commodity Price Cycles in Three Charts,” World Bank Blogs, January 2022, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/commodity-price-cycles-three-charts [17] Carmen M. Reinhart Vincent Reinhart Christoph Trebesch, “Global Cycles: Capital Flows, Commodities, and Sovereign Defaults, 1815-2015,” NBER Working Paper Number 21958, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21958/w21958.pdf [18] Ewald Nowomy, “Emerging Markets – Boom and Bust,” Special high-level meeting of United Nations Economic and Social Council with the World Bank, IMF, WTO and UNCTAD, April 2014. [19] While growth expectations are priced in, surprises are not, see for instance, Joseph Davis, Roger Aliaga-Diaz, Charles Thomas, Ravi Tolani, “The outlook for emerging market stocks in a lower-growth world,” Vanguard Research, (2013), pp. 8. [20] Guillermo Calvo, Leonardo Leiderman, and Carmen Reinhart, “Inflows of Capital to Developing Countries in the 1990’s,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 10, No. 2 (1996), pp. 124. [21] Peter Blair Henry, “Stock Market Liberalization, Economic Reform, and Emerging Market Equity Prices,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 55, Iss. 2 (2002) [22] Frankde Jong and Frans de Roon, “Time-varying market integration and expected returns in emerging markets,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 78, Iss. 3 (2005). [23] Karl V. Lins, “Equity Ownership and Firm Value in Emerging Markets,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 38, No. 1 (2003), pp. 159-184; Subodh Mishra, “Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, (February 24, 2019), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2019/02/24/corporate-governance-in-emerging-markets-3/, Accessed August 20, 2022. [24] Joseph Davis, Roger Aliaga-Diaz, Charles Thomas, Ravi Tolani, “The outlook for emerging market stocks in a lower-growth world,” Vanguard Research, (2013). [25] Das Mitali, Mohapatra Sanket, “Income inequality: the aftermath of stock market liberalization in emerging markets,” Journal of Empirical Finance Vol. 10, Iss. 1-2 (2003), pp. 217-248. 7 [26] “Gini Coefficient by Country 2022,” World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gini-coefficient-by-country, Accessed August 20, 2022; Lucas Chancel et. al., “World Inequality Report 2022” World Inequality Database (2022); Stephan Klasen, “What to do about rising inequality in developing countries?” Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network, PEGNet Policy Brief, No. 5 (2016). [27] Alistair Dieppe (ed), Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers, and Policies, (Washington DC, the World Bank Group, 2021). [28] Feenstra, Robert C., Robert Inklaar and Marcel P. Timmer (2015), "The Next Generation of the Penn World Table" American Economic Review, 105 (10), 3150-3182, available for download at www.ggdc.net/pwt [29] Excluding MSCI’s “WAEMU” [30] Vladimir Popov and Jomo Kwame Sundaram, “Are developing countries catching up?” Cambridge Journal of Economics No. 42, Vol. 1, (2018), pp. 33-46. [31] Considering that the developing country list includes countries like Iceland (2017 HDI score of 0.94) and South Korea (2017 HDI score of 0.9) which are in fact quite wealthy countries, it is safe to say these scores are skewed slightly upwards. [32] World Economic Forum, “The Global Social Mobility Report 2020 Equality, Opportunity and a New Economic Imperative,” January 2020. [33] Carlotta Balestra et. al., “Inequalities in emerging economies Informing the policy dialogue on inclusive growth,” OECD, SDD Working Paper No. 100 (2018). [34] Kemal Dervis and Zia Qureshi, “Income Distribution within Countries: Rising Inequality,” Brookings Institution, August 2016. [35] The Economist, “Are emerging economies on the verge of another “lost decade”?” April 30, 2022; Jonathan Wheatley, “Emerging markets: all risks and few rewards?” Financial Times, Feb. 14, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/9cc2826b-dcd2-49c5-a408-7de043d24a79 [36] Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson, Why Nations Fail: the Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown Business, 2012), pp. 73-75. [37] YiLi Chien, “What Drives Long-Run Economic Growth?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, June 1, 2015. [38] Geroski, P. A., 'Where Do New Technologies Come From?', The Evolution of New Markets (Oxford, 2003; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Nov. 2003); Brian Kelly et. al., “Measuring Technological Innovation Over the Long Run,” NBER Working Paper 25266 (Revised Feb 2020). [39] Jon Pietruszkiewicz, “What are the Appropriate Roles for Government in Technology Deployment?” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, White Paper Task No. 7000.1000 (1999); Peter Singer, “Federally Supported Innovations: 22 Examples of Major Technology Advances That Stem From Federal Research Support,” The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (2014); Nassim Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (Penguin, 2007). [40] Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), pp. 81. [41] Tom Palmer, “Foreward,” in Jean Philippe Delso, Nicolas Lecaussin, and Emanuel Martin, eds. Anti Piketty (Washington DC: Cato Institute, 2017) pp. xv-xvi. [42] Lutz, W., Crespo Cuaresma, J., & Abbasi‐Shavazi, M. J. (2010). Demography, education, and democracy: Global trends and the case of Iran. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 253-281. [43] Alina Rocha Menocal et. al., “Why corruption matters: understanding causes, effects and how to address them: Evidence paper on corruption,” UK Department for International Development, January 2015. [44] Yongquan Cao, Yingjie Fan, Sandile Hlatshwayo, Monica Petrescu, and Zaijin Zhan, “IMF Working Paper: A Sentiment-Enhanced Corruption Perception Index, WP/21/192” IMF, July 2021 [45] The Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Worldwide Educating for the Future Index,” 2019, https://educatingforthefuture.economist.com/the-worldwide-educating-for-the-future-index-2019/, Accessed August 26, 2022; Emma Wadsworth-Jones (ed), “The Freedom of Thought Report 2020,” Humanist International, 2020. [46] Richard Feynman, Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (W.W. Norton, 1985), pp. 243. [47] Fran Collyer, Global patterns in the publishing of academic knowledge: Global North, global South,” Current Sociology Vol. 66, Iss. 1 (2016), pp. 56-73; Layal Liverpool, “Researchers from global south under-represented in development research,” Nature News, September 17, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02549-9, Accessed August 22, 2022. [48] The Economist, “Ghana, an oft-lauded African economy, is back for a 17th bail-out,” August 5, 2022. [49] The Economist, “Iraq’s parliamentary plague,” August 1, 2022. [50] The Economist, “Ranil Wickremesinghe must persuade suffering Sri Lankans to endure more pain,” July 28, 2022. [51] Carmen M. Reinhart, Kenneth S. Rogoff, This Time is Different, Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton, 2011) [52] Richard Wike, Laura Silver, and Alexandra Castillo, “Many Across the Globe Are Dissatisfied with how Democracy is Working,” Pew Research Center Report, April 29 2019; Dambisa Moyo, “Why Democracy Doesn’t Deliver,” Foreign Policy, April 26 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/26/why-democracy-doesnt-deliver/, Accessed August 25, 2022. [53] This point being one of the main arguments of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a more academic formulation of which is sociologist Robert Michels’ “Iron Law of Oligarchy.” [54] Autocracies and Economic Development: Theory and Evidence from 20 th Century Mexico Jörg Faust; Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung Vol. 32, No. 4 (122), Neue Politische Ökonomie in der Geschichte / New Political Economy in History (2007), pp. 305-329 (25 pages), pp. 312 [55] Cory Welt and Rebecca Nelson, “Russia: Domestic Politics and Economy,” Congressional Research Service (September 2020), R46518, pp. 28 [56] The Economist, “Much of Russia’s intellectual elite has fled the country,” August 9 2022.

Comments