Wittgenstein is a Shepherd, and the Market His Herd

- Nathan Decety

- Jan 17, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 22, 2021

Wittgenstein wrote about the intricacies inherent to communication. In Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) he discussed the difficulty of sharing thoughts and ideas. Wittgenstein believed that humans communicate by sharing pictures. Words allow us to “make pictures of facts.” When someone describes something, their counterpart “sees” that picture in their mind. Those pictures can include all the senses, including taste and smell. But it’s often very difficult to convey a good picture into the mind of another, they have the wrong picture of what one means. A major difficulty is that humans are not machines, they have an incomplete and potentially vague image of whatever they’re describing, as psychological research in memory and conscience has shown. Further, while there are immense number of bits of information available, we are only able to actually take in and process a comparatively small number in the first place. When sharing a picture with someone, we only are able to share the most salient and evident parts, which is usually just a segment of action.

When I think of something and try to describe it, I am not only limited by the availability of information but also the language I can use. Good communication is efficient communication, the number of words necessary to convey a point must be limited; one doesn’t always have the tools (words and phrases) available for describing what one pictures. Even when there are the tools, sometimes those available are actually non-descriptive about what is being described. Saying ‘I am sad’ is actually a presentation of a whole spectrum of negative emotions that includes diverse feelings including melancholy, regret, or mournful – all of which are vastly different. Alternatively when trying to be precise, perhaps when I say ‘I am miserable,’ does my counterpart understand that perhaps I am deeply mournful and yearn for better days, or perhaps do they understand that I am deeply uncomfortable at this moment because I lost 10K in the market?

Wittgenstein also claimed in Philosophical Investigations (1953) that when people communicate they are often playing a certain “game.” There can be different meanings behind many statements, and confusion can arise when people fail to understand the game being played by their counterpart. For example, if a close friend exclaims, “you’re always late!” you might think they are playing a game called ‘stating facts’ which would include claims such as: ‘France was an important player in WWI.’ On the defensive, you may answer that you are rarely late, and maybe the couple instances in question were not representative because of some unforeseen difficulties (i.e. traffic last Sunday). But maybe they’re not playing a ‘stating facts game,’ maybe they’re playing a ‘I need attention game.’ You’re always late could be a stand-in for ‘I want you to spend more time with me,’ or ‘I wish you would prioritize me over other events and people.’ If so, your defensive response would have seemed a little calloused and perhaps caused them to feel rejected.

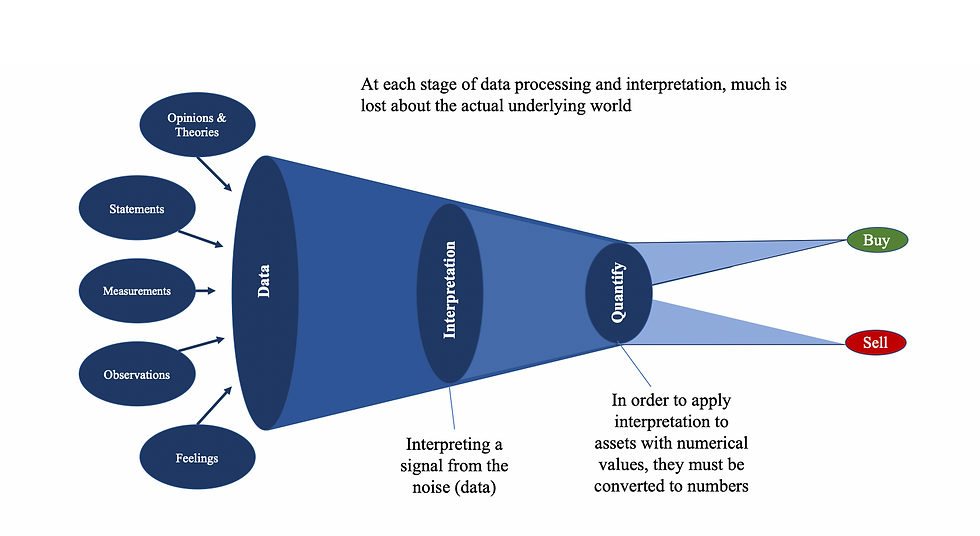

To summarize some of these bottlenecks and limitations, please see the flow of communications below.

Let us now turn to asset prices – in particular equity values. The price of a stock is, in theory, equivalent to the expected future flow of cash unclaimed by liabilities. In practice, it is equivalent to a price agreed upon by a seller and a buyer, and their determination of a ‘correct price’ is derived from its theoretical valuation.[1] That valuation is based on an unknown and uncertain future; the seller and buyer both technically have access to the same public information yet have their own reasons for wanting to sell or buy the asset.

The question that we’ve really been discussing is what is this information, and what are these reasons to buy or sell?

In order to simplify the flow of information, organizations use similar verbiages, jargon, and methodologies (i.e. throughput and simple English). For example the use of numbers generates order and clarity. Everyone understands that $300 sold is better than $150 sold. But that simplicity can be insidious. What does it really mean that $300 of product or service was sold when it comes to the price of stock? Is it predictive of future cash flows, or changes in market conditions, or rival offerings, or new technologies, etc.? Does $300 being sold suggest the firm is extremely embedded in the society and fulfilling a consequential service? Or does it mean that the workers have established really good relations with one particular client as a result of a fortunate hiring decision? Maybe the $300 was a one time thing and no one realized, because the seller made a poor impression on the buyer so they won’t be a repeat customer, the possibilities are potentially vast.[2] We must not forget that investors represent only a section of the importance of a firm: there are many different interest groups within and without an organization, the purpose of firms is to be embedded in society and provide services or goods that are in demand, and to coordinate and allocate resources efficiently to that end.

Information has to be converted to numbers and profits or loss in order for it to be relevant for buying or selling a security, otherwise it is irrelevant. Because there is similar language (technical terms/jargon/etc.), it somewhat limits the possible interpretations. The world appears to be simpler than it really is. While there is plenty of data, each interpretation and each time that data is shared the message becomes more simple and takes on a life of its own. But the process of conversion itself deletes information and creates seeming certainty where there should be confusion and precisely the absence of certainty. Consider for instance if a company had a generally good year (for whatever actual reasons), which causes profits to increase by 10%; everyone ‘understands’ that higher profit is good so the price of the stock rises, and some make decisions based on the asset value having increased; overall however the original uncertainty of the firm’s place and value-add for the future has diminished. The result is a world that is slightly separated from reality. Because the information stating that profit increased by 10% is the one that is looked at by everyone and used to make decisions, it can cause herding.

On the flip side, a tenant of Kurz’ rational expectations, likewise formulated by W.V. Quine (1951 – Two Dogmas of Empiricism) is that there is a plethora of logically consistent hypothesis and interpretations that can be applied to a given series of facts. Clearly the signals can be interpreted in different ways, by virtue of the information being presented in such a standardized manner it narrows the universe of possible interpretations.

It is far easier to take a path of least resistance and take information at face value (increase in profit of 10%) than to dig deeper and try to understand everything – which is not always necessary in the first place, nor cost effective. This piece is not as an attack on the market because there isn’t necessarily a better way to share data, but to point out that there is an important role for skepticism to play because available public material information is not all relevant information. Why is this important? Because market efficiency implies that prices reflect all available information; but by virtue of this information being limited that means that prices only reflect a certain subset of available information at a specific point in time.

Moving on to Wittgenstein’s view of the “games” inherent in communications, we find a similar pattern in markets. While organizations are made up of, and interact with, entities with different needs and goals, their equities are traded between individuals seeking to make money in accordance with agent-specific time horizons and risk preferences. A priori therefore the information presented in the market will be related, presented, and interpreted through that lens. In other words, since market participants are looking to make money and not necessarily to understand the truth, that limits the potential number of communication games that can be taken into account.

The “communication game” played by most firms is to showcase – with incomplete or imperfect data – some generally positive image of themselves. Meanwhile, investors putting time into research to make a decision to buy or sell must use information that will be relatable to the conditions of the firm, leaning on whatever third-party data they can but also on the reports by the firm itself. But consider the incentives against selling: potential future gains and dividends, the cost (and unlimited downside) of short-selling, the ponzi-like characteristics of the market (see Schiller’s irrational exuberance, 2015), and the information put out by the firm (which is positively skewed). History is against sellers. Investors expect – as a natural consequence of capitalistic growth and return of capital – that there be a long-term average growth rate for most asset classes and investments.

To further elucidate, apply, and depict this argument as a cohesive whole, consider Bryan Cranston’s character in Breaking Bad: Walter White, and let us focus on his meticulousness. The viewer often saw Walter behaving meticulously: careful with numbers, precise at removing crust from sandwiches, unable to suffer a wobbly table. It fit with the narrative description of his profession in chemistry. However making the jump of Walt being meticulous for some tasks to thinking that it is an important and clear attribute of his personality is not necessarily a seamless extrapolation; is Walt meticulous about everything or just specific tasks? Is Walt meticulous 25% of the time but the viewer only sees that 25% and so thinks Walt is truly meticulous 100% of the time? Now that we’ve defined him as meticulous, additional evidence enhances that view (the availability heuristic and confirmation bias in psychology). Forecasts of how Walt would behave would have to take his meticulousness into account as a major part of his character. A general description of Walt to share with others would then be “he is a meticulous and prideful schoolteacher turned criminal” but that simple narrative and model do not do him or his story justice, even less so if a person with similar characteristics had actually tried going through a similar set of events in real life. A extrapolation of a few actions and moments were interpreted as a major character trait that now serves as a descriptor for the individual!

In summary, by virtue of the processes to interpret data and apply those interpretations to a share, a great deal of nuances are lost and assumptions made. Narratives are formed and congealed into numbers that then influence the price of a stock. Casting off those nuances means that shares also reflect a simplified world which can be divorced from underlying conditions. When everyone sees similar information, it limits the potential number of hypothesis that can be drawn, and so herding is - to a point - inevitable.

[1] Even though some humans are being replaced by robotic traders, those algorithms still have to be written based off some theory, some person’s idea. Algorithmic trading is just an extension of someone’s ‘mathematical hot take.’ [2] It is a fact that so and so dollars were raised by selling this many items. However, consider the many ways companies can hide profits and losses; clever financial accounting can disguise a company on the verge of bankruptcy, and shield a profitable one from high taxes. As a reflection of this biased opacity, at the University of Chicago Booth School in 2020, there are 8 advanced courses taught by 15 professors that delve into the intricacies and opportunities available through accounting. A forecast with numbers presents false clarity about an uncertain future, if someone says I feel great, that could be anywhere on the spectrum of ~7-10/10, but saying “I feel 10/10” is far less vague, yet represents the exact same feeling except with more apparent- but superfluous - certainty. Expecting long term returns of 5% is almost meaningless when forecasting next year’s returns – known to be extremely volatile and never return the long term average.

Comments